The Chicken Dance Case: Mi-STAR Students Solve a Mystery

Tuesday, July 3, 2018

A mysterious affliction hits a Michigan public school. Many of the teachers are inexplicably breaking out in show tunes and irritating 1980s novelty dances, and to cope with the crisis, the building is placed under quarantine. Enter the plague sleuths: students piloting Mi-STAR's Unit 6.2: Investigating and Modeling Body Systems.

“They are looking for a pathogen that's affecting the adults in our school,†explains Gwen Windiate, who teaches science at Christa McAuliffe Middle School, in Bay City. “It's called RAD disease, for Random Acts of Dancing.â€

The students are charged with finding out what causes RAD, how it attacks the body, how it spreads, and how to cure it using tissue engineering. “Since we're in quarantine, they have to do the investigation themselves, and they get regular updates from the CDC [Centers for Disease Control] reporting on the results of their discoveries,†Windiate says. “They've found that RAD is caused by a virus in the staff lounge coffee pot, and that it affects the nervous system.â€

Windiate has taught several Mi-STAR units and is an enthusiastic supporter of the curriculum, but Unit 6.2 is something special. She pauses during an interview to address a few students gathered in her classroom “Girls, how do you like the unit we're doing?†she asks. All thumbs go up. “They love it, love it, love it,†she reports. “This one really has grabbed their attention. It's been so fun, and it's so real. Diseases are something they can all relate to.â€

RAD has also lent itself to some cheery theatrics on the part of the school staff. “We filled teachers in around the school, so out of nowhere they'd start doing the chicken dance,†Windiate says. Later, as the students closed in on solving the problem, the principal generously agreed to provide samples for the tissue engineering lessons. “He came into our class with bandages all over his face.â€

Christopher DeVantier is piloting the unit with seventh graders at Hart Middle School, in Rochester Hills. “It's a lot of fun,†he agrees. “The kids were really excited at the start, and six weeks into it they are just as enthusiastic.â€

It's not simply that the unit is engaging, he adds. It's also eye opening. “They've discovered that getting something approved by the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] is really rigorous, and before, they didn't have an appreciation for that. Now they know you can't just put Cinnamon Toast Crunch in a box and sell it as breakfast cereal. There's lots of testing involved.â€

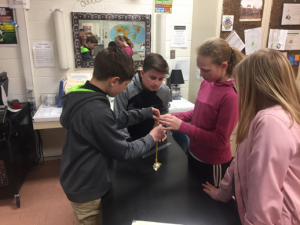

DeVantier was particularly impressed with the unit's pasta tower exercise, which involves spaghetti, rigatoni, tape and a marshmallow. This activity teaches students about optimization, part of their preparation for addressing the Unit Challenge. Later in the unit, in their role as tissue engineers, they will evaluate medical devices, combining their best features to create the most optimal device to help fix their teachers’ brains.

“The kids who are really handy got a chance to shine, while the A kids had to sit back a bit and watch,†he said. “I was shocked to see the results they came up with. Then they had to see if they could improve their designs by looking at other students' towers, and it was cool to see how they made them better.â€

This exercise illustrates Mi-STAR's efforts to help all students understand scientific and engineering principles—not just the ones headed for advanced STEM degrees. “There are some really talented kids out there who might not be a good fit for college but have amazing hands-on skills, and I always try to make them aware of opportunities in the blue-collar professions,†he says. “We need to find a way to put our arms around those kids. They are very important for the future of our society.â€

DeVantier's main subject is math, so he has also been pleasantly surprised at how straightforward the Mi-STAR curriculum has been to implement. “I have a limited science background, but it's still very easy for me to understand,†he says. “The units are getting better, more teacher friendly. I love Mi-STAR's vision, and I'm especially excited to be working on this unit.â€

For Windiate's students, one lesson in particular stands out. “They got to look at real tissue—sheep brains—under the microscope, and they really liked that,†she says. In addition, one of the unit's primary values may lie in how it hones students' critical thinking skills, especially in an era when anyone can pose as an expert by posting to Facebook or slapping up a webpage.

“It was difficult for them to understand the concept of bias at first,†she says. “Now they know that you have to look at the source. Is someone making money off this? Are they really an expert? Even if your source is educated, their background might not be in the right field.â€

Now, as students evaluate source material, “they will go for the one with the best research,†she says. “That's standing out for me, how practical this lesson really is and how it addresses something that's very serious: the credibility of your sources.â€

She also appreciates the scope of the unit, which incorporates the life and physical sciences, public health and even government. “How cool is it that sixth graders are learning about the CDC and the FDA?†Windiate asks. “And the whole thing is wrapped around solving a mystery. I've done five or six Mi-STAR units, and this one is hands down my favorite.â€

Unit 6.2Â is now available for teachers who have taken Mi-STAR's professional learning program.

GET Mi-STAR NEWS BY E-MAIL!

Copyright © 2026 Mi-STAR

Mi-STAR was founded in 2015 through generous support provided by the Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation. Mi-STAR has also received substantial support from the National Science Foundation, the MiSTEM Advisory Council through the Michigan Department of Education, and Michigan Technological University.